- Details

Team W6YX has a been chugging along, participating in the annual ARRL Earth-Moon-Earth (EME) contest. The contest consists of three weekends. The first weekend is for frequencies above 2GHz, usually in September. In October and November are two contest weekends for amateur radio frequencies bands below 2GHz. The goal is to contact as many stations as you can using the surface of the moon as a passive reflector. Voice, CW, and digital communication modes are

used. We built from scratch, modified existing designs, modified existing hardware, modified existing code or wrote code from scratch to build our 5 band EME station. W6YX regularly contacts stations around the world via a lunar path using 10.368GHz, 2.304GHz, 1.296GHz, 432MHz and 144MHz.

Our team has been busy in recent years with non amateur radio aspects of our lives. This has prevented us from putting on a 5 band contest effort. Due to time constraints we didn’t give a 2018 update, so it’s fitting we start there. Our unexpected issues from 2017 continued. As summer of 2018 was ending we decided to optimize our 10GHz station. Usually we pick a project to concentrate our efforts on before the EME contest. Knowing our beam pattern will give valuable information in determining why our dish is performing notably worse than what it’s theoretically capable of. We setup a signal generator feeding a dish 5km away.

We scanned the vicinity of this signal source using our 4.6m dish in 0.1º increments, measuring its amplitude using Linrad’s excellent signal level measurement functionality. After several hours spent painstakingly manually scanning, we had a spreadsheet full of data points used to produce a plot of our dish’s beam pattern.

The pattern alone did not explain the lack of expected performance. With no single or easy point of optimization we could complete before the contest, we decided to enter our station into the contest as-is.

While testing our 10GHz station, we noticed our echos off of the moon were greatly attenuated.

Further inspection showed a critter had crawled and nested in our feed horn. Unfortunately it did not survive the dielectric heating during the transmission periods of our TWT amplifier. The remains were too charred to identify the species of the critter. The melted Kapton wave guide seal (over 400ºC/750ºF) gave indication of the temperatures involved.

Fortunately this issue was easy to repair.

Unfortunately right before the start of the contest, our dish elevation system exhibited failure resulting in very high elevation motor current draw. The current draw caused the failure of a 2ohm 100W current limiting resistor in series with the motor. We found a temporary solution by placing the manual mechanical brake part way between the on and off position. This allowed the failed braking system just enough pressure to keep the dish from falling in elevation, but not too much brake pressure that the motor couldn’t over power. We couldn’t simply bypass the current limiting resistor to the motor with out spending time recalibrating the controller used to drive the motor. To replace the blown 2ohm 100W resistor, we found some stranded wire cut to a length that resulted in 2ohms. Unfortunately the wire jacket was not able to withstand the 260ºC temperatures the motor drew, even with the brake partially released.

After charring this makeshift wire resistor, we ended up putting together a combination of power resistors in series and parallel to produce 2ohms. However, this also proved ineffective, as the resistors quickly began to overheat. An elegant solution was found. We placed the resistors in a bucket of water. If the water didn’t boil, we knew the resistors were safe, under 100ºC.

After these hurdles and missing the first night of the contest, we were able to make it back on the moon the second night and scored a respectable 2nd place in the multi-operator, all mode, 10GHz category. Our team has worked extremely hard over the years building our station in capability, bands, reliability and usability. Team W6YX’s ARRL EME contest performance over the past 7 years reflects this.

2012- 4th place in the multi-operator, all mode, all band category

2013- 5th place in the multi-operator, all mode, all band category

2014- 2nd place in the multi-operator, all mode, all band category

2015- 1st place in the multi-operator, all mode, all band category. Would have placed top three in each of our 5 bands if our efforts were divided.

2016- 1st place in the multi-operator, all mode, 1.2GHz category

2017- 1st place in the single-operator, CW mode, 1.2GHz category

2017- 2nd place in the multi-operator, all mode, 10GHz category (using the call N9JIM)

2018- 2nd place in the multi-operator, all mode, 10GHz category (using the call N9JIM)

2019- Projected based on electronic logs received: 1st place in the multi-operator, all mode, 1.2GHz category (using the call K6MG), and 2nd place in the multi-operator, all mode, 144MHz category

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In 2019 team W6YX had another successful ARRL EME contest. We put in a more limited effort this year, operating 1296 and 144 MHz. The contest was not with out its share of unexpected surprises. We had planned to also operate our 10GHz station, but a last minute elevation position readout issue prevented us from getting our 10GHz signal on the moon for the first time in 5 years. Our elevation syncro position to digital converter box developed a strange intermittent offset.

We have since replaced it with a working unit, but requiring at least 0.1º position readout to track the moon, it was not feasible to devise an alternative solution overnight to save our 10GHz contest entry. Critters continued to chew through our coax and cables over the prior year, so we spent contest time fixing the damage and adding shielding to prevent further gnawing.

Given how busy our team was with non ham activities, we decided 2019 would also be a limited contest effort for us. When we put in a limited effort, we typically use calls signs of various team members, and save the W6YX call sign for our more competitive contest entries. We chose to enter our 7.9m diameter dish on 1296 MHz, and our four 10m long boom yagi, cross polarity 144 MHz antenna array individually, each band operating casually using different call signs.

Our 1296MHz station was performing intermittently up to the contest. The azimuth readout would intermittently shift by 90º, causing tracking issues. Our amplifier’s power supply would intermittently shut off, interrupting contacts. Our 144MHz station was performing great however. No issues observed while testing before the contest. Unexpectedly, our 1296MHz station cleaned up its act and performed great over the two contest weekends. We operated casually, abandoning the station shortly after the moon rose for our EME friends over the Pacific. Given our evening moon rise, we didn’t have the energy to operate through the night and morning. Relative to a station near the Eastern USA shore, we have about 3 hours less moon time with Europe, the hub of EME activity, per lunar pass. This 18 hour deficit across all three contest weekends is a challenging deficit to overcome. The level of activity between Europe and the Pacific is significant. To put it in perspective, typically we we contact two or three times more stations from Germany alone than all of our friends over the Pacific combined.

The first weekend of the under 2GHz portion of the contest resulted in unexpected failure of our 144 MHz station. Not long after our moon rise we completely lost our vertical polarity transmit and receive capability. Several minutes later we also lost our horizontal polarity. This was unfortunate, as the hours after moon rise on the first weekend is the most active and fruitful for making contacts at a fast rate. Inspection showed we had fried our high powered transmit/receive RF relays.

The temperature inside the relay got hot enough to crack its internal ceramic contact guides. The internal relay contact use to be shiny gold and symmetric in shape.

It was not feasible to foresee the cause of the failure. The azimuth motor for our 144MHz EME array uses a DC motor, whose direction is changed via an H bridge composed of industrial mechanical relays.

The coil of these relays use the same 28VDC supply that powers the coils of our transmit/receive RF relays. One industrial relay started to fail by sticking in the on position. This caused our array to drift away out of control. Natural human instinct is to pull the array’s direction control joystick in the opposite direction that the array was stuck running. Unfortunately, due to the stuck relay in the H bridge, the direction reversing caused a short in the H bridge, which caused a short of the 28VDC power supply, which caused the high powered transmit/receive RF relay coils to disengage while 1500W of RF was flowing through its contacts. The contacts were hot switched off. As the pictures above show, the damage to the contacts was severe, evaporating much of the metal. The sticking H bridge relay problem occurred during the 2018 contest, and was forgotten about. We suspect our RF relays were hot switched and damaged in 2018, but did not completely fail until the 2019 contest. Such exotic failure modes can not be anticipated. It is not feasible to exhaust so much of our resources building a station resilient to such obscure failures. We replaced the RF relays the following day and were back on the moon the second day. Drenching the sticky H bridge relay with penetrating lubricant and manually massaging its actuator prevented it from sticking for the rest of the contest.

Both bands of our station performed great the second weekend. On 1296 MHz we even called CQ via SSB and had a nice chat with VE6BGT (55/57). On 144 MHz we never recovered from losing invaluable contest time while having mutual moon time with Europe, but scored well none the less. Based on the 194 electronic logs the ARRL received as of December 23rd, 2019, we are projected to rank 1st place in the multi-operator, all mode 1296MHz category, and 2nd place in the competitive multi-operator, all mode, 144MHz category. Pleasing results given our team’s limited effort and misadventures.

- Details

| Who: | Invited Speaker, Ralph Simpson | |

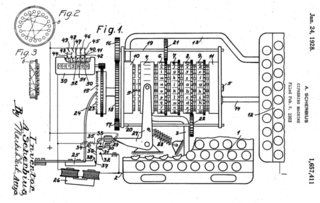

| What: | The German Enigma Machine: The Secret Battlefield of WWII, featuring a real, working machine from WWII! | |

| Where: | Packard, Room 202 101 |

|

| When: | Tues, Jan 14th, 7:30pm |

The German Enigma Machine: The Secret Battlefield of WWII

The story of the Allies overcoming the odds and breaking the Enigma is a story of innovation, intrigue, and deception; which significantly shortened the war and ushered in the age of computers. The success of cracking the Enigma was kept secret for 29 years after the end of WW2, despite tens of thousands people working on the effort in the UK and US. This secrecy is especially incredible for us living in the age of the internet, WikiLeaks, and Edward Snowden. Over 35,000 Enigma machines were manufactured, but only 350 are known to exist today.

|

Ralph Simpson worked in the computer industry for 32 years, at IBM and Cisco Systems. He is now retired and volunteers at a local museum, History San Jose. He wrote a book on cipher history called, _Crypto Wars: 2000 Years of Cipher Evolution_. He is also an avid collector of cipher machines, which you can see on his website, CipherHistory.com. Ralph lives in San Jose in a restored Victorian house, which is also home to his Cipher History Museum and a very understanding wife. They have three grown children.

- Details

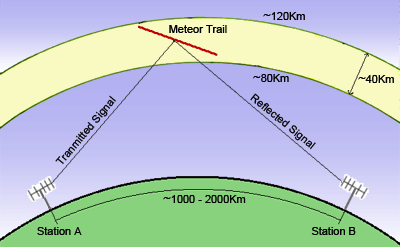

What: Bounce radio waves off of meteor trails

Where: W6YX Shack, Site 530

When: Tuesday, August 13th, 7:30pm

Come to our shack to enjoy the Perseid Meteor Shower in both the visible and radio spectrum, as we attempt to make radio contact with other stations across the Western US by bouncing radio signals off of ionized meteor trails. A truly unique communication experience.

Guests are welcome. No license is required for participation. Bring a friend!

- Details

| Who: | Invited Speaker, Bjorn Forsberg | |

| What: | Talk on radios from WW1 | |

| Where: | Packard, Room 202 | |

| When: | Tues, March 13th, 7:30pm |

The Stanford Amateur Radio Club, W6YX, will hold its monthly meeting Tuesday, March 13th at 7:30pm in Packard 202 with invited guest speaker Bjorn Forsberg. (This talk was originally scheduled in February but was postponed.)

WW1 Communication Equipment

Join us to hear about the history of World War I military equipment and communication as it began in Europe, as well as how it propagated to the U.S. Come see examples of both European and U.S. equipment from that period, including the Telefunken EV 72 amplifier (1912) complete with the von Lieben tube, which is an extremely rare piece of equipment.

Biography

Bjorn's career has been centered in satellites, where he's worked over thirty years with Philco Ford (now Space Systems Loral). He's also worked in the semiconductor industry with Raytheon and CTC in the Los Angeles area. Bjorn got his Ham license in 1958 as SM5UR in Sweden and is still active, mostly on 80 meters AM with heavy iron (750 lb). He's collected antique radios since he immigrated to the US in 1968, but the collection has swung over to military radios and then mostly to WW1-era military equipment.

- Details

Before we start this story, lets rewind back to the 2016 ARRL Earth-Moon-Earth contest. Our 10GHz TWT Amplifier died shortly before the event. We still manged to get our 4.6m, Cassegrain dish on the air with a borrowed solid state amplifier. Jumping to 2017 we repaired the damaged silicone potted filament transformer in hopes to get the station on the air for the DUBUS 3cm EME contest which coincided with ARRL Field Day.

Unfortunately, after a very successful transformer repair the amplifier was still sick.

Even if the amplifier worked, we still wouldn’t have been been able to get the station on the moon. We discovered the azimuth gear drive had seized. Like the potted transformer, motor removal and replacement was not an easy task.

With the 2017 ARRL EME contest not far away, team W6YX got to work getting our 5 moon bounce bands on the air. Last time we entered this most challenging all bands - all modes section, team W6YX won first place! An impressive feat. Our California Pacific coast location means we have limited mutual moon time with Europe, where the hub of moon bounce activity is. EME operators, can you imagine having 3 hours less mutual moon time with Europe every single moon pass compared to a station on the Atlantic coast? 18 fewer hours combined mutual moon time with Europe across all three contest weekends! This is a tremendous disadvantage we consistently overcome with effective engineering choices, and efficient operating using Linrad Software Defined Radio extensively on all bands.

Personal commitments and the quantity of work prevented us from getting all 5 bands on the air for the 2017 ARRL EME contest. We decided to concentrate on only getting our 10GHz station on the air for the microwave weekend of the event. The weekend before the contest we got azimuth working and got the amplifier producing power again. However, the amplifier still had a mysterious intermittent problem. The 4kHz reference for the helix supply DC – DC converter would randomly fail to function. Removing the 200lbs (90kg) amplifier, hauling it to the work bench, hauling it back to the dish and reinstalling it is not an easy task.

Unable to reproduce the 4kHz reference problem, as it seemingly went way, we reinstalled the amplifier. It is worth mentioning a team member did quote “problems that go away on their own, come back on their own”. We enjoyed listening to our voice echos off of the moon Tuesday September 5th! Better than expected performance, given our station has yet to be optimized.

Feeling content, all we had to do is park the dish and wait three days for the contest to start. Three hours before moon rise on contest day, we were met with an unpleasant surprise. The amplifier was not producing power! Hastily in the dark, we removed the amplifier to trouble shoot.

Yes, as expected, the 4kHz reference was failing to start.

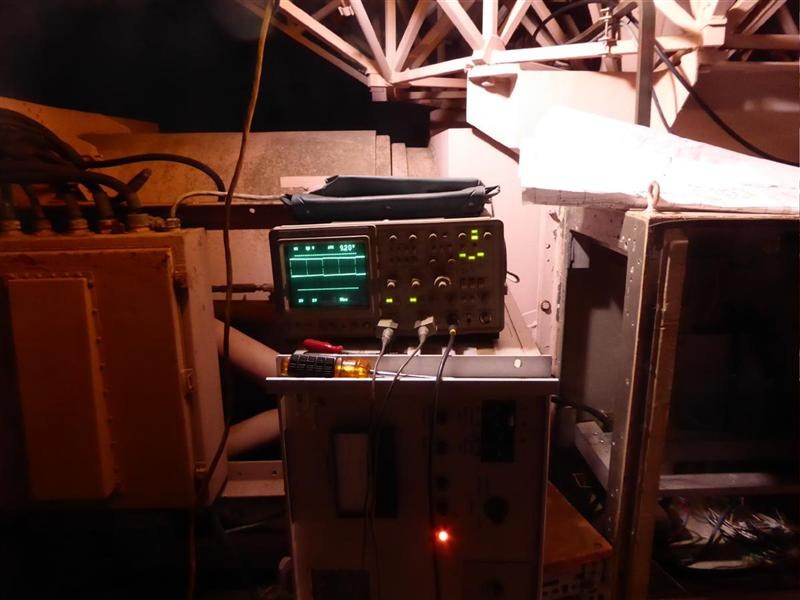

Pressure only increased, as the moon rose above the horizon while we scoped and probed the amplifier in the dark.

Lunar declination wasn’t near its maximum, meaning our time with Europe was even more limited. We hurried to repair the amplifier. A team member noticed a blip on the scope as the capacitors discharged while powering down. A desperately needed clue! The 4kHz reference was showing signs of life. We were stumped by the cause of this problem. Transformer-saturation based oscillator designs are well before our time. Unintuitive terrain, just like trying to figure out how to use oscilloscopes that lack LCD touch screens. What we affectionately refer to as the bad ‘ol days. While analyzing the schematic, we empirically discovered if we quickly blip the power to the TWTA off and on, the oscillator would sometimes start!

Not a true fix by any measure, but we can work with this. Perfection is the enemy of good enough and our moon time with Europe is limited. We soldered a wire tapping into the 4kHz reference signal and ran it out side of the amplifier housing. The plan was to reinstall the amp and blip power to it until we saw a 4kHz signal on the scope. Once this happened, we would erect the dish and get on the moon!

In our excitement, we go to move the dish towards the moon. Nothing happened. The F1EHN tracking software was not talking to our dish micro-controller. How could this subsystem fail? Everything was working great 72 hours prior. Expedited trouble shooting revealed the problem. Within three days, rodents fully chewed through our RS232 control cable!

Further analysis revealed the power/relay control cable was also chewed! This explained the mysterious short that developed between some of the conductors in this cable a few weeks earlier.

We’re not done yet. Even the transmit and receive coaxes were chewed up!

No time for a real fix. We’re losing moon time with Europe! We can solder, heat shrink and tape later. Now is the time to pry shielding braid strands from touching the exposed center conductor of the coax and twist control cable wires together. Perfection is the enemy of good enough, especially when you’re losing precious moon time with Europe!

With the amplifier working and our cabling mended, we were able to get on the moon at last!

Only to find out the last station in Europe packed it in for the night. Fortunately we still had our Northern American, Australian and Japanese friends to look forward to. A 1m diameter dish running 50W was the smallest station we worked, and he was an arm chair copy thanks to WSJT-X’s QRA64-D digital mode.

The next evening, we were ready at moon rise contacting our 10GHz European friends.

The event organizers picked a great condition weekend for microwave moon bounce. Libration spreading on 10GHz was very reasonable. We ended up with around a dozen contacts in the log and had a great time! Everyone in our team contributed significantly. The lesson learned was to never ever give up. Sometimes, you just have to choke the crane.